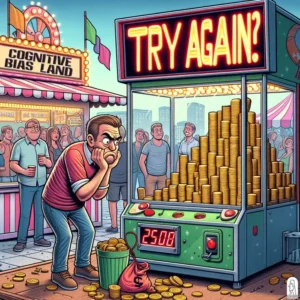

In the 1960s, the British and French governments jointly developed the Concorde supersonic jet—a revolutionary but economically doomed project. Despite knowing the aircraft would never be profitable, both governments continued pouring billions into development. When questioned, officials famously responded, “We cannot stop now, after having already spent so much.”

This perfect example of the sunk cost fallacy demonstrates our powerful tendency to continue investing in losing propositions simply because we’ve already invested significant resources. From failed relationships to money-losing business projects, this cognitive trap costs individuals and organizations billions annually while causing immense emotional distress.

What Exactly is the Sunk Cost Fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy occurs when we consider irrecoverable past investments when making decisions about the future. These “sunk costs”—whether financial, temporal, or emotional—should theoretically be irrelevant to rational decision-making. Yet psychologically, we find it incredibly difficult to ignore them.

Classic Examples Include:

-

Sitting through a terrible movie because “I already paid for the ticket”

-

Remaining in an unhappy relationship because “I’ve invested five years already”

-

Continuing a failing business project because “we’ve spent so much already”

-

Eating too much at a buffet because “I need to get my money’s worth”

The Psychology Behind the Trap

Several interconnected psychological mechanisms drive this irrational behavior:

Loss Aversion

Research shows losses psychologically impact us about twice as powerfully as equivalent gains. Abandoning a project feels like accepting a definite loss, while continuing offers the illusion of potential recovery.

Commitment Consistency

Humans have a deep-seated desire to appear consistent. Once we’ve committed to a course of action, we feel psychological pressure to maintain that commitment, even when evidence suggests we should change direction.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Emotional Investment

The more emotion we’ve invested in a decision, the harder it becomes to abandon it. This explains why people stay in toxic relationships or continue pursuing dreams long after they’ve become unrealistic.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Responsibility Avoidance

Admitting failure often feels more painful than continuing with a failing course of action. The sunk cost fallacy allows us to postpone this uncomfortable moment of truth.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The Economic Reality vs. Psychological Perception

Rational economic theory dictates that only future costs and benefits should influence decisions. From this perspective:

Sunk Costs = Irrelevant

Money, time, or effort already spent cannot be recovered and should not factor into whether you continue investing.

Future Costs/Benefits = Everything

The only question that matters is: “Going forward, will additional investment yield positive returns?”

Yet our brains stubbornly refuse to follow this logic. The psychological pain of “wasting” previous investments overwhelms our rational assessment of future outcomes.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Real-World Consequences

The sunk cost fallacy impacts lives and organizations in profound ways:

Personal Finance

Individuals hold losing investments too long, throw good money after bad in home renovations, or continue gambling to recoup losses. One study showed investors were 1.5 times more likely to sell winning stocks than losers, despite tax advantages for doing the opposite.

Business Strategy

Companies continue failing projects because of historical investment rather than future potential. Notable examples include Microsoft’s long persistence with Windows Phone and countless “zombie projects” that drain resources because nobody will pull the plug.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Military History

The Vietnam War exemplifies sunk costs on a geopolitical scale, where successive U.S. administrations continued escalating involvement partly because “we can’t let previous sacrifices be in vain.”

Personal Relationships

People remain in unhappy marriages, friendships, or business partnerships because of time already invested rather than future happiness potential.

Breaking Free: Practical Strategies

Overcoming this deep-seated bias requires conscious effort and specific techniques:

1. The “Zero-Base” Decision Framework

Periodically pretend you’re starting from scratch. Ask: “If I hadn’t already invested anything, would I choose this path today?” This mental reset helps separate past investments from future potential.

2. Precommit to Exit Criteria

Before starting any significant investment, define clear conditions for abandonment. For investments: “I will sell if it drops 15% below my purchase price.” For projects: “I will reassess if we miss these three milestones.”The Sunk Cost Fallacy

3. Seek External Perspective

Consult someone unaware of your previous investments. Their unbiased view often reveals what you can’t see through the fog of sunk costs.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

4. Reframe “Wasted” Resources

View previous investments as tuition rather than losses. The knowledge gained has value, even if the specific project fails.

5. Practice Opportunity Cost Awareness

Regularly ask: “What could I achieve if I redirected these resources elsewhere?” This shifts focus from recouping losses to maximizing future gains.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

When Sunk Costs Should Influence Decisions

While generally fallacious, there are limited circumstances where considering past investments makes sense:

Strategic Signaling

Sometimes continuing a project demonstrates commitment to stakeholders, though this should be a conscious strategic choice rather than a psychological trap.

Learning Curve Benefits

If previous investment has created expertise that reduces future costs, this legitimate future benefit shouldn’t be confused with recouping sunk costs.

Contractual Obligations

Legal or moral commitments might require honoring past investments, but these should be explicit rather than psychological.

Organizational Defense Mechanisms

Companies can build structures to minimize sunk cost thinking:

Separate Decision-Makers from Project Champions

Ensure someone uninvolved in initial funding decisions evaluates continuation.

Create “Kill Committee” Rotations

Designate teams specifically tasked with identifying failing projects without emotional attachment.

Celebrate “Intelligent Failures”

Reward teams that shut down failing projects early, creating psychological safety for cutting losses.

The Emotional Intelligence of Letting Go

Ultimately, overcoming the sunk cost fallacy requires emotional maturity. It means accepting that:

-

Failure is information, not identity

-

Resources are finite and opportunity costs are real

-

Consistency is only valuable when you’re consistently right

-

Courage sometimes means stopping rather than continuing

Conclusion: The Wisdom of Knowing When to Quit

The sunk cost fallacy reveals a fundamental truth about human psychology: we are storytellers who hate unfinished narratives. We want our investments—financial, emotional, or temporal—to have meaning and payoff. This desire for narrative completion often overrides rational calculation.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Yet the most successful investors, entrepreneurs, and individuals share a common trait: the wisdom to know when to quit. They understand that the only thing more wasteful than losing previous investments is compounding those losses by throwing good resources after bad.The Sunk Cost Fallacy

As Warren Buffett famously advised, “Should you find yourself in a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.”The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The ability to ignore sunk costs isn’t just an economic principle—it’s a lThe Sunk Cost Fallacyife skill. By learning to make decisions based solely on future potential rather than past investments, we free ourselves to pursue what truly moves us forward, unburdened by what we leave behind.The Sunk Cost Fallacy