the Science of Habits

the Science of Habits You wake up and check your phone. You drive to work on autopilot. You find yourself scrolling through social media without deciding to. These actions are habits, the invisible architecture of daily life. Research from Duke University suggests that habits account for about 40 percent of our behaviors on any given day. Understanding how habits work isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s a practical skill that can help you waste less time, be healthier, and achieve your goals. The science reveals that habits are not about willpower; they are about systems. The Habit Loop: The Brain’s Autopilot System At the core of every habit is a neurological loop consisting of three parts. This model, popularized by Charles Duhigg in his book The Power of Habit, is the key to understanding why habits exist and how to change them. 1. The Cue: The Trigger for Automatic Behavior The cue…

Negative Visualization

n the year 60 AD, the Stoic philosopher Seneca found himself facing execution. For years, he had practiced imagining the loss of his wealth, status, and even his life. Now, as the Roman emperor Nero’s soldiers surrounded him, this mental preparation allowed him to face death with remarkable calmness. He turned to his grieving friends and said, “Where are your maxims of philosophy? Where that learning you’ve been preparing for so many years against this exact moment?” Seneca’s composure wasn’t accidental—it was the result of regularly practicing what the Stoics called premeditatio malorum: the premeditation of evils. This practice, now known as negative visualization, remains one of the most powerful psychological tools for building resilience and finding contentment. What is Negative Visualization? Negative visualization is the deliberate practice of imagining that we have lost the people, possessions, or circumstances we value. The Stoics recommended regularly contemplating: The loss of loved ones The…

The Map is Not the Territory

In 1931, Polish-American philosopher and scientist Alfred Korzybski introduced a concept that would revolutionize fields from psychology to systems theory. During a lecture, he suddenly interrupted himself to fetch a packet of biscuits. As he munched on them, he announced to the stunned audience: “Ladies and gentlemen, I am eating the map, not the territory.” This dramatic demonstration illustrated his central thesis: “The map is not the territory“—our mental representations of reality are not reality itself. The models we create in our minds are necessarily simplified, incomplete, and sometimes dangerously misleading versions of what actually exists. What Does “The Map Is Not The Territory” Really Mean? At its core, this principle distinguishes between three crucial levels:The Map is Not the Territory 1. The Territory: Objective Reality This is the actual world as it exists, in all its complexity and detail. It’s the raw data of existence, independent of our observation or…

The 80/20 Principle

The 80/20 Principle.In 1897, Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto made a fascinating observation in his garden. He noticed that roughly 20% of the pea pods produced 80% of the peas. Being an economist, he extended this observation to wealth distribution and discovered that 20% of the Italian population owned 80% of the land. This simple observation would eventually become one of the most powerful productivity principles in history: the 80/20 rule or Pareto Principle. The core insight is both simple and profound: in most areas of life, a small minority of causes (around 20%) create the majority of results (around 80%). Understanding this principle can revolutionize how you work, live, and think about achievement. The Mathematics of Effectiveness The 80/20 principle isn’t about exact mathematical precision—it’s about recognizing consistent patterns of imbalance: 20% of customers typically generate 80% of revenue 20% of products usually account for 80% of sales 20% of your activities…

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

In the 1960s, the British and French governments jointly developed the Concorde supersonic jet—a revolutionary but economically doomed project. Despite knowing the aircraft would never be profitable, both governments continued pouring billions into development. When questioned, officials famously responded, “We cannot stop now, after having already spent so much.” This perfect example of the sunk cost fallacy demonstrates our powerful tendency to continue investing in losing propositions simply because we’ve already invested significant resources. From failed relationships to money-losing business projects, this cognitive trap costs individuals and organizations billions annually while causing immense emotional distress. What Exactly is the Sunk Cost Fallacy? The sunk cost fallacy occurs when we consider irrecoverable past investments when making decisions about the future. These “sunk costs”—whether financial, temporal, or emotional—should theoretically be irrelevant to rational decision-making. Yet psychologically, we find it incredibly difficult to ignore them. Classic Examples Include: Sitting through a terrible movie because “I…

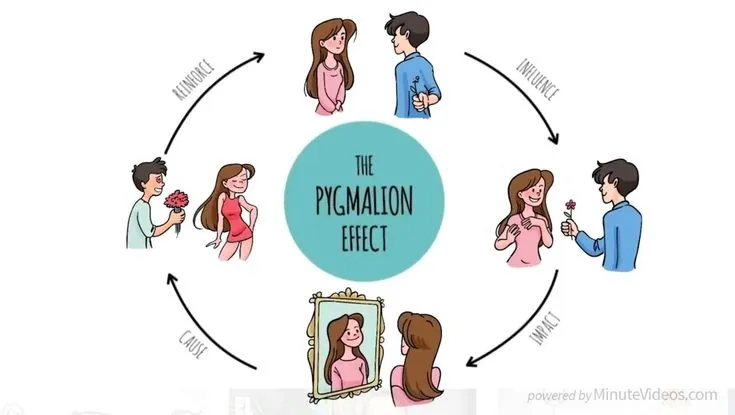

The Pygmalion Effect

In 1965, Harvard psychologist Robert Rosenthal and elementary school principal Lenore Jacobson conducted one of the most controversial and illuminating studies in educational psychology. They told teachers that certain students in their classes—randomly selected—had been identified through a special test as “academic spurters” who would show remarkable intellectual growth in the coming year.The Pygmalion Effect The results were astonishing. When tested eight months later, these randomly chosen students actually showed significantly greater IQ gains than their peers. The teachers’ expectations had created a self-fulfilling prophecy. This phenomenon, where higher expectations lead to improved performance, became known as the Pygmalion Effect, named after the Greek myth of a sculptor who fell in love with a statue he created, which then came to life.The Pygmalion Effect The Psychology Behind the Phenomenon The Pygmalion Effect operates through several interconnected psychological mechanisms:The Pygmalion Effect 1. The Climate Effect When we have high expectations for someone,…

The Bystander Effect

On March 13, 1964, a young woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was brutally attacked and murdered outside her Queens apartment building. The case became legendary not just for its brutality, but for the reported fact that 38 witnesses watched from their windows and did nothing to intervene or even call the police. While subsequent investigations revealed the original reports were exaggerated, this tragedy sparked the interest of psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley, who began a series of groundbreaking experiments that uncovered one of social psychology’s most disturbing phenomena: the bystander effect. Their research revealed that the more people who witness an emergency, the less likely any one individual is to help. The Science Behind the Effect: Why We Freeze The bystander effect occurs due to several interconnected psychological processes that activate when we’re in a group: 1. Diffusion of Responsibility In a crowd, individuals feel less personal responsibility to act.…

The Fermi Paradox hidden secretas

The Fermi Paradox In 1950, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Enrico Fermi was deep in conversation with colleagues at Los Alamos National Laboratory. The discussion, touching on flying saucers and the potential for faster-than-light travel, eventually shifted to the likelihood of intelligent life existing elsewhere in our vast universe. Amidst the chatter, Fermi suddenly blurted out a question that has since become legendary in scientific circles: “Where is everybody?“ This simple, almost childlike question encapsulates what we now know as the Fermi Paradox. It highlights a profound contradiction: our universe is unimaginably large and old, suggesting that intelligent life should be common, yet we have found no definitive proof that anyone else is out there. The Logic of the Paradox The power of the Fermi Paradox lies in its step-by-step, logical reasoning: Countless Suns: Our Milky Way galaxy alone contains an estimated 200 to 400 billion stars. Habitable Worlds: Many of these stars…

Web3 blockchain secrets

What is “Web3 blockchain If you’ve heard the term “Web3” but find the concept confusing, you’re not alone. Touted as the next evolution of the internet, Web3 represents a fundamental shift in how we think about digital ownership, privacy, and online interaction. But beyond the buzzwords and technical jargon lies a simple idea: an internet where users own their data and digital assets rather than surrendering them to tech giants.blockchain To understand Web3, it helps to see how we got here and where we might be going next in the internet’s ongoing evolution.blockchain The Internet’s Evolution Web1 (1990s-Early 2000s): The Read-Only Web Static websites like digital brochures Limited user interaction Most people were consumers, not creators Examples: Early Yahoo, basic HTML sites blockchain Web2 (2000s-Present): The Read-Write Web Dynamic, interactive platforms User-generated content Social media, cloud computing Centralized control by big tech companies blockchain Examples: Facebook, YouTube, Google Web3…

Compounding Interest

Compounding Interest Albert Einstein reportedly called compound interest “the eighth wonder of the world” and “the most powerful force in the universe.” While the attribution might be apocryphal, the sentiment is mathematically sound. Compound interest is the fundamental principle behind most wealth creation, yet many people fail to harness its full power because they don’t understand how it works or start using it early enough. Compounding Interest At its simplest, compound interest means earning interest on your interest. This seemingly small distinction creates exponential growth over time, turning modest regular investments into substantial wealth. Understanding this concept is more valuable than any single investment tip or stock pick. Compounding Interest The Basic Math Compound interest differs from simple interest in one crucial way: Simple Interest: You earn interest only on your original investment. Example: $1,000 at 5% = $50 yearly interest Compound Interest: You earn interest on your original investment…